Even if superhero movies aren't your thing, the furor around Marvel's latest offering in their cinematic universe, Age of Ultron, has been pretty unavoidable. Amid accusations of sexism following the release of the film, Joss Whedon suddenly deleted his Twitter and everyone went nuts. In an interview explaining his decision, Whedon told BuzzFeed, "I saw a lot of people say, 'Well, the social justice warriors destroyed one of their own!' It's like, Nope. That didn't happen." And he's right. Apart from the fact that he, in his own words, left Twitter because it interrupted his creative process, SJWs hardly claim Whedon as one of their own. His previous work, despite its popularity and quality, has drawn plenty of criticism, especially as feminism has evolved over the years.

The bar for feminist work has been set higher than it was when Buffy first aired and Whedon hasn't done much to elevate his content to reach that bar, but still seems to insist on receiving his Ally of the Year trophy for achieving the bare minimum. His language in the BuzzFeed interview hints at someone who's feeling unappreciated by a fanbase he thought he'd locked down. "Believe me," he says, "I've been attacked by militant feminists since I got on Twitter. That's something I'm used to. Every breed of feminism is attacking every other breed and every subsection of liberalism is always busy attacking another subsection of liberalism, because god forbid they should all band together and actually fight for the cause." As a general rule of thumb, if someone is using the phrase "militant feminist" unironically, especially a straight white guy, that person is probably not a feminist.

The only brands of "feminism" that other feminists attack tend to be exclusionist brands of faux feminism, branches that exclude women of color, trans women, or queer women. As the popular saying goes: "my feminism will be intersectional or it will be bullshit." Whedon's self-described feminism has certainly not been everything it could be. There are valid critiques to make about his work, from a liberal perspective: the racist depiction and origin story of the First Slayer on Buffy, the lack of Asian actors on Firefly and especially his reasoning that this was fine because Summer Glau "kind of looked Asian," the attempted rape and resulting romance on Buffy, his obsession with the "break the cutie" trope, and, off-screen, the way he handled Charisma Carpenter's pregnancy on Angel.

With that said, the real problem of Age of Ultron is a problem with Marvel, and their lack of female characters. Black Widow is a de facto stand-in for All Women in the Marvel cinematic universe (MCU) because she's the only one. It becomes nearly impossible to give her a plot that doesn't become at least partially representative for what the writer and Marvel think All Women are or should be. It's not sexist in and of itself for Black Widow to pursue a romantic relationship or struggle with her forced sterility, but it's easier to read these stories as sexist when they're the only real stories about women we get in the movie.

Wanda Maximoff (aka Scarlet Witch) gets a minor character arc about becoming an Avenger, but there's not enough room in the movie to do her service. Maria Hill is mostly there to fire a gun and deliver exposition. Helen Cho is a plot device, but at least one that is respected and given a bit of personality, or at least as much of one as can be expected for her amount of screen-time, which is more than can be said for Laura Barton. The movie is too big, too crammed, to give proper consideration to all of its characters. It's no easy feat to tie in three different franchises and a TV series (Marvel's Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D.) into one movie, especially a movie that has to function as a sequel to Avengers and a prequel to Infinity War in its own right. The end result is a movie that is sloppily written, and the specific claims of sexism can mostly be explained by failures in the script.

The scene that has received the most criticism occurs between Black Widow (Natasha Romanoff, played by Scarlett Johansson), and the Hulk (Mark Ruffalo's Bruce Banner). Bruce is trying to convince Natasha that a romance between the two of them would be a future-less disaster because he can't have a family. Natasha reveals that as part of her training in the Red Room, she was forcibly sterilized. Then she tells him that he's not the only monster on the team. The monster line in particular, I think, is just bad writing. I don't think it's supposed to refer to her forced sterilization, rather the "red in her ledger" from Avengers, the trail of bodies she's left in her wake. But it's unclear. You can certainly read it as Natasha saying she's a monster because she can't have children, and if in fact that was the intention of the line, someone needed to clarify that that was not the case, that she had a monstrous thing done to her, but that that thing didn't make her monstrous.

As a character, she has valid feelings about a complicated, terrible past, but when we have to consider that she's the only female Avenger (a problem Whedon did, to his credit, try to solve in the first film), it becomes problematic to associate monstrosity and her ability to bear children. In fact, with enough exploration, the story of women's bodies being policed and regulated has potential for real feminist commentary. The problem is you can't fit that in a two hour movie that has to do a dozen other things. The problem is two minutes of flashback/dream sequence doesn't make up for the gaping lack of a solo film. For the same reason, it also becomes complicated to give her a love interest, and again, poor writing makes this a harder sell.

There were certainly moments of connection between Natasha and Bruce in Avengers, but those who find their romance sudden in the sequel aren't wrong. Age of Ultron clearly takes place after some time has passed, even between the rest of the movies in the MCU. We get a token reference to Steve and Sam's on-going search for Bucky that began at the end of The Winter Soldier, we get a reminder of Selvig and his role in The Dark World, but there's clearly too much to keep track of. Tony has somehow done a complete reversal on his decision to destroy his suits at the end of Iron Man 3, and in fact, now has a whole unexplained robotic army under his control. I think it's safe to assume that something happened between Bruce and Natasha offstage between Avengers and Age of Ultron as well.

When Natasha flirts with him at the bar, it feels like something she's done before. Bruce even brushes it off as something that she does habitually. It's possible she's worked up to this over a period of months, and the relationship between Natasha and the Hulk is clearly closer than it was during Avengers. She's now the one responsible for tranquilizing the Hulk when the battle's over, and Hulk shows incredible trust in her. But filling in these blanks and investing emotional stakes in something this abrupt is a lot of work for audiences who are already trying to keep up with a dozen cameos, casual fans who are trying to keep track of the world-building and the plot, and uber fans who are looking for easter eggs. There's a lot going on in this movie already. It's a lot to ask for an audience to do so much work building a relationship, especially when a lot of longtime fans still haven't separated the MCU from the comics, where the two have no romantic history. The end result is a lot of "telling" to save the time it would have taken to "show." Multiple characters remark on an obvious or long-standing romantic tension between Bruce and Natasha, which doesn't do a lot to get audiences on board emotionally, even if it fills in the plot.

It shouldn't be sexist for Natasha to want a romantic relationship, and it's not even out of character for her to long for escape. Literally every other Avenger has a romantic past. The difference is that (with the exception of Clint Barton, see below) all of these romances have at least one whole movie of dedicated development and exploration, if not two or three. A few glances in Avengers is not an effective substitute. Without the time to develop the relationship naturally, it seems shallow. Like the monster line, it's easy to read this as sexist, either a source for Bruce's angst or a gross assumption that of course the woman is going to hook up with at least one of the guys.

It doesn't help that the MCU has teased a multitude of pairings between Natasha and the male Avengers, as Jeremy Renner famously (and obnoxiously) noted. Natasha got as much romantic tension with Steve in The Winter Soldier and Clint in Avengers as she got with Bruce. It makes the choice to pair her off with Bruce feel arbitrary. There were ways around this, if Whedon had put in a little more effort. He could have eased into the relationship more, could have included more set-up in Avengers, could have invested in more scenes that actually demonstrated their affection for each other, rather than a lot of lines that insist on its existence. There were a lot of ways he could have made it more palatable, but in the end, nothing is a substitute for a whole movie dedicated to Black Widow where a romance could have been explored fully and naturally, in a way that wouldn't make it definitive of her as a character.

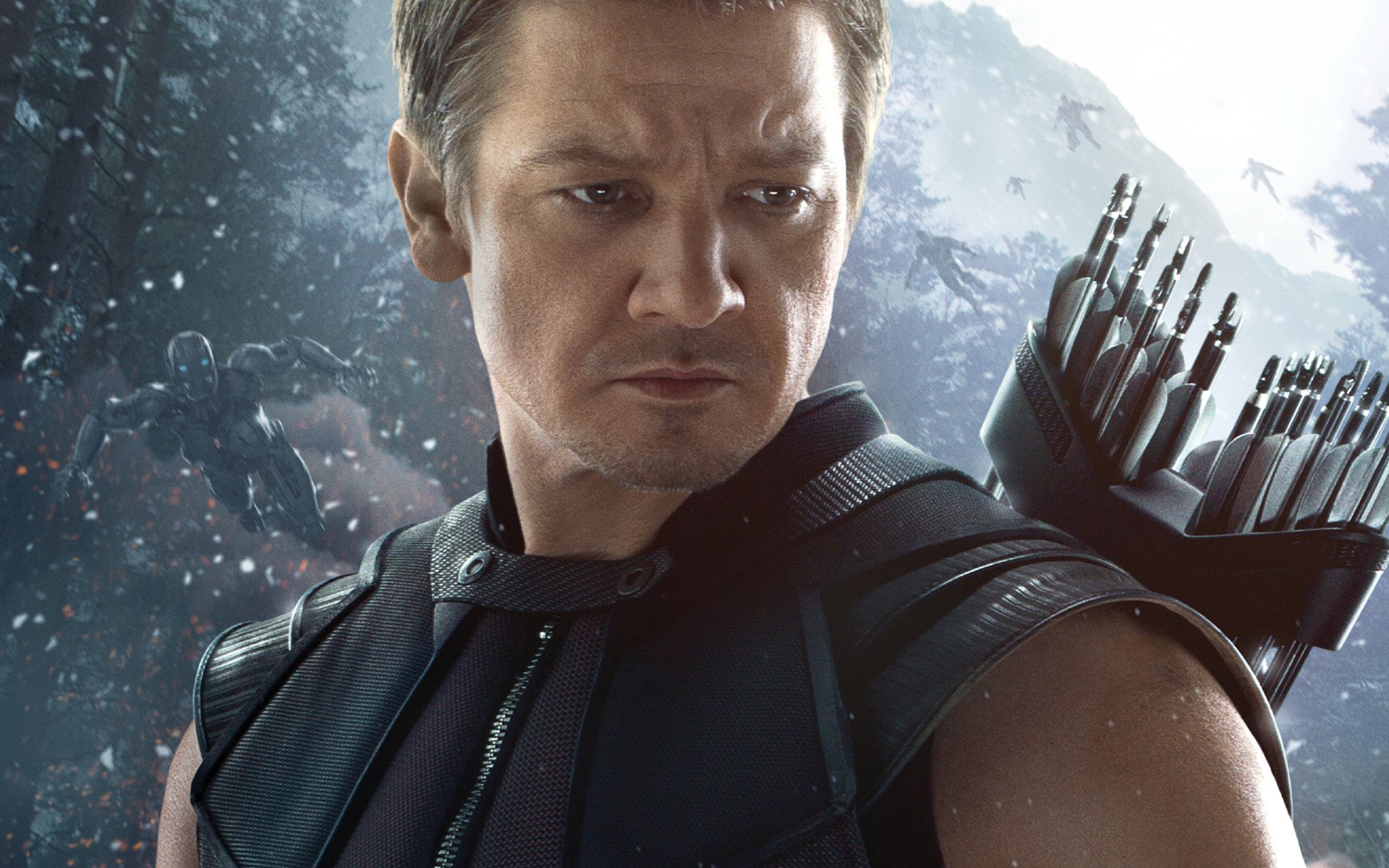

It's not just Natasha who suffers from a lack of development. Clint (aka Hawkeye, portrayed by Jeremy Renner) suffers from a similar problem in the movie. He was brainwashed into non-existence for the majority of the first movie, and his treatment here isn't much better. Instead of actual character development, we get a manufactured reason to care about him: an idyllic, loving, heretofore unmentioned, cardboard cutout family. It's the laziest, cheapest way to raise the stakes on him as a character. If anything were to happen to him in the final fight (as it was heavily hinted it might), the audience wouldn't be upset because something happened to Clint, we'd be upset that he was leaving behind a pregnant wife and two kids. In the comics, Clint has a rich backstory. Even as the least useful member of the team, he has a unique role to play as an "everyman" among badasses, a character Whedon has historically loved (eg. Xander from Buffy, Wash from Firefly), but without the time to dedicate to his character, Whedon took a shortcut.

Iron Man's rape joke (his line about reinstating prima nocta) is another aspect of the movie that has been heavily criticized, and is perhaps the hardest to excuse, not least because it was a line that was changed from the original, funnier line in the trailer. Like the antiquated gendered slur that upset audiences in Avengers, this seems like a pointless use of old language to get away with a gross, sexist line. Whedon's excuse in Avengers is that the line is uttered by a villain, and was therefore in character. Frankly, the rape joke is in character for Tony Stark. Tony was specifically created by Stan Lee to be unlikeable. He's sleazy, arrogant, a war profiteer, and, generally, an asshole. The problem is, in the MCU, he's also the most popular Avenger, by a lot. Loki was also a hugely popular character, but at least it was obvious we weren't supposed to admire him, regardless of a number of fans who seem determined to excuse his genocidal ambitions.

These movies are kept at PG-13 for a reason; they're marketed to kids, especially boys, who are looking for heroes to emulate. Thus far, in the movies, Iron Man has been a role model, at least more so than in the comics. He's tried to correct his mistakes. He's been an example of scientific exploration and ingenuity. He's Robert Downey Jr., which means he's funny and quick-witted, and people want to be him. That's where the line becomes a problem. Whether it's in character or not, you can't really have a heroic character making rape jokes, especially if you're a writer who has a history of using the rape of women or the threat thereof as character development for men (see: Spike in Buffy or the planned gang-rape of Inara on Firefly). The most frustrating part of the joke was that there was no reason for it. Tony's "fair but firmly cruel" line from the trailer was still an asshole comment, and it was funnier. There was no reason for a rape joke.

But in spite of all that, I think this movie was actually a step up for Whedon. I know I wasn't the only one who instinctively recoiled at the introduction of Wanda Maximoff in the post-credit scene of The Winter Soldier. She looked exactly like one of Whedon's infantalized, insane, badass babydolls, the problematic "kill the cutie" trope he can't seem to let go of. Drusilla from Buffy, River from Firefly, Echo/Caroline from Dollhouse... he's done this kind of thing before and it was a valid concern that he might do it again, but he resisted that with Wanda. He might be learning! And in terms of sexism, even within the MCU, Guardians of the Galaxy was certainly much more egregious than either Avengers or Age of Ultron. The fact is, if we're looking for the source of the sexism, Marvel itself is the real culprit.

By the admission of Marvel's own employees, the company has no interest in marketing itself to women and girls, much less making itself palatable to female audiences. Regardless of a number of noncommittal statements about maybe doing a Black Widow solo some day, or even the announcement of Marvel's first female and black superhero franchises (Captain Marvel and Black Panther, respectively), the company has shown zero commitment to diversifying its roster, and in fact bumped both of those movies back even further to make room for another fucking Spider-Man movie, and not even a Miles Morales Spider-Man, or Spider-Gwen: another fucking Peter Parker, because I guess a whole trilogy and a reboot just wasn't enough. Marvel is definitely the bigger problem here, but just because he's operating under a lot of restrictions for a sexist company doesn't mean Whedon holds up as a feminist ally, and certainly not to the degree he seems to think he has earned.

Overall, the main problem people have with Whedon is his insistence on allyship on his terms. He wants to be held up as King Feminist, but he also wants to indulge in his more sexist tendencies as a writer. When criticized, he pouts and claims the movement is destroying itself, rather than take responsibility and make an effort to take the criticism constructively. When a man wants to call himself a feminist but doesn't feel any responsibility to listen to concerns of female fans, that man is not a feminist. I think tumblr user gyzym put it best in a recent post responding to the criticism:

"say you’re a doctor, right? and you go to medical school and everything, you learn the things modern science has to teach you about healing the human body, and then you’re sent out into the world to first do no harm. that’s great! woo-hoo! congrats to you, and best of luck. but as a doctor, what you’re supposed to do is keep up with modern medical advances, you know? that’s what your patients expect of you; that’s what leonard “bones” mccoy expects of you; that’s part of the territory. and if you don’t do that – if, say, a patient comes to you with a problem that would have been treated with arm amputation when you graduated from medical school, but has since been found to be completely curable with a quick shot, your patient is probably going to be pretty angry if you cut their fucking arm off! and i mean, look, this is an imperfect analogy for a lot of reasons [...] the point is that a medical degree is not assumed to be the end of your learning about medicine, because that would make no sense – we’re learning and discovering new things about the human body all the time. being part of the field means keeping up.

this same thing is true of feminism – and, for that matter, of all the other -isms. social issues are not static things; like medicine, they are are about living, breathing human beings. like medicine, we are learning and discovering new things about them all the time. we learn as people who have not gotten a chance to speak before find their voices, or a space for their voices. we learn as the distance of history allows us a perspective we didn’t have before. we learn as children who grew up in abusive systems get old enough to break them down. we learn as we unlearn things that we have believed to be true for years, decades, and centuries, and which turn out to have been harmful all along. it is an ongoing process. it is work. willingness to do the work is part of what it means to adopt the title."At the end of the day, if Joss Whedon wants to insist on the title, he needs to do the work.

No comments:

Post a Comment